– Hey! 👋 I’ve written some new insights about this topic at a more recent blog post

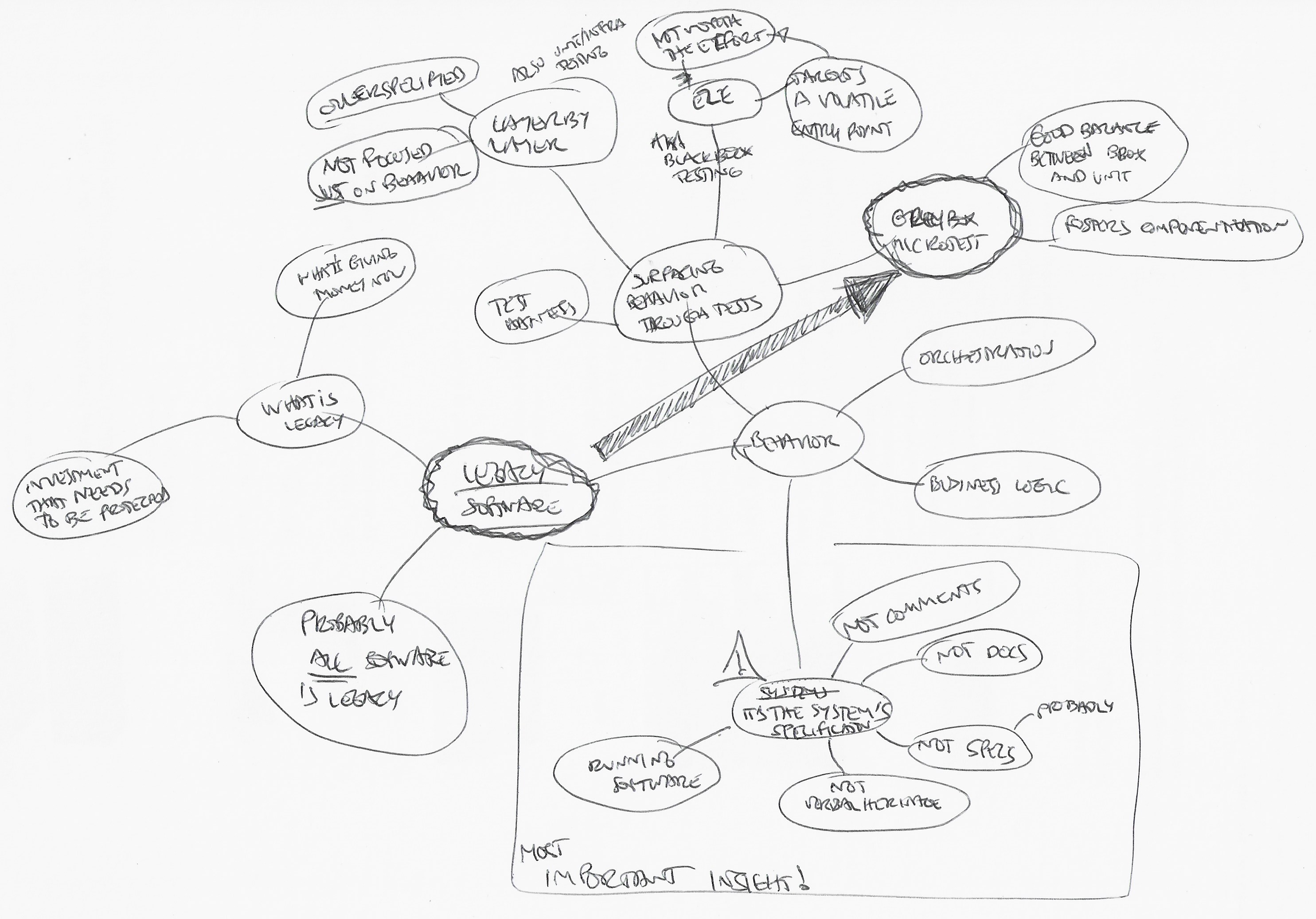

Grey-box Microtest TDD is my favorite testing approach these days, and after reflecting on it, I think it’s because I mainly deal with legacy software.

First, let’s clear the air about legacy software: almost all software becomes legacy once it hits a production environment and customers start using it. Legacy software is providing valuable service to users right now and ultimately brings money to the organization behind it.

I’m not here to judge any idiosyncratic and contextual reasons for putting a specific software version in front of users. What’s relevant is that organizations make investments by doing that, and our role is to protect them.

We can protect an investment daily through many activities, such as ensuring that the software we produce can be easily removed, maintained, or evolved with the lowest possible cost. It often means that releasing a new version won’t add any unknown or uncontrolled risks or that we have identified any deficiencies and have a strategy to deal with them.

However, I’m talking about software that’s already there: we don’t have control over how it was produced. We can only worry about what we do with it moving forward, and, in my experience, the first problem always is understanding the system’s behavior.

My central insight about this is that a system’s behavior is its specification. Running software beats documentation, oral tradition, code comments, and most tests. The exceptions are bugs (i.e., unwanted behavior) and tests that treat the system as a black box in some way.

Not all types of tests do a good job at it:

- Tests about boundaries between software layers target internal behavior, which is not our goal here: we want to describe the system’s observable behavior, i.e., outputs and side-effects.

- Pure end-to-end and black-box tests are costly to produce, maintain and run, and they get outdated because they drive the system from volatile entry points.

To be clear: you still need to write these 👆 tests. It’s just that it probably won’t be practical for you to describe your system’s behavior with them.

Grey-box Microtest TDD tests, however, do a great job at it. They foster an excellent balance between driving your system as a black box from your tests while simplifying some aspects of the entry point you choose to drive it with.

So. Microtest TDD relies on the usage of a gray-box testing style. The tests read like they’re black box, but they’re written using white-box info, things only someone inside the code could know. We do this risky judgment-centric thing to ship more value faster.

I make my interpretation of Grey-box Microtest TDD in my daily work by combining it with another powerful concept: cohesive software components, which is a matter for another article, but the gist of it boils down to two statements:

- Every business or vertical section and every infrastructure or horizontal section of the system should be represented by a cohesive component.

- Every cohesive component has a public entry point - a public API - that the system uses to provide value to users, and no other part of the system can access the component’s internal assets.

For example, at DNSimple, where I work, we provide our users with commercial and Let’s Encrypt ACME certificates, which translates to a certificates directory where we put all the business logic code related to our vertical component about certificates. Any part of the system that needs to deal with certificates can do so through (and only through) a facade at Dnsimple::Certificates.facade.

This design provides excellent entry points for our tests because facades provide high level of abstraction business operations that make sense from the user’s perspective. This is pivotal when trying to describe the system’s observable behavior.

The “white box” part of tests about the cohesive components I’ve described consists of knowing how to get the component’s facade and set up the test scenario. The rest can be approached as a black box test by describing the behavior in test titles and asserting outputs and side effects.

A good description of the system’s behavior at such a high-level incision point with comprehensive assertions enables us to defer design decisions and explore and evolve the SUT’s internal structure safely and cheaply.

We get a lot in return from investing in working like this. It increases our confidence while extracting a component from the legacy part of the system, and coming back to introduce changes always feels more straightforward and smoother.